LA's Three-Fold Housing Crisis

Explaining the three distinct - but related housing predicaments in Los Angeles

Last month, I was with my kids at State Historic Park just outside of downtown Los Angeles when I met a fellow dad holding his young child. He and his wife are young professionals who moved to Los Angeles from Minnesota about three years ago with their four children (!) under five. They live near the park in Chinatown in a two-bedroom apartment with their kids. I asked them how that was going, sharing a little bit about my story. He said it was tight; living near the park made it more tolerable, but they couldn’t sustain it much longer. Homeownership was probably never going to be a realistic option in the city. They hoped to find a new place to rent that would be better for their family, ideally a small townhouse, but also recognized that finding such a place would be quite challenging.

I found this family’s frustrating situation to be a helpful frame for thinking about the scope of LA’s housing crisis. Their family was not in financial distress; they were young professionals who chose to come to LA by choice in search of opportunity. Yet within 15 minutes, our conversation turned to the subject that housing was a massive constraint in their life (I promise I was not the one who injected the subject into the conversation). This is a story many share across the city. What made them an outlier was that they had decided to push through the housing constraints of living in Los Angeles to have four kids.

Right now, the City of Los Angeles is in the middle of an every-decade process where they re-examine the city’s housing strategy to see whether it allows building the homes the city needs. The state has required this process for over 40 years, but this is the first cycle where the state has gotten serious about holding cities accountable, given the depth of the housing shortage in the city.1 For context, in the last cycle, Los Angeles was expected to build 82,000 units over eight years; in this cycle, the city is expected to build 456,000 units. So far, the city has been falling far behind that target, with only 46,054 units permitted according to HCD’s data dashboard – putting the city at only about 10% of its target. Not Great, Bob!

In response, the city has tailored a suite of programs to try to address the housing crisis. The one with the most impact is the city’s new “Citywide Housing Incentive Plan” (CHIP). In theory, CHIP is supposed to create incentive programs that will accelerate the city’s ability to meet its housing targets. Given the city's current plan, I will explore how that is unlikely to happen in my next post. But for today, I think it's important to take a step back and be more precise about why this effort is important. I think you can illustrate the housing crisis in Los Angeles by discussing three types of people at different levels of the housing market.

Crisis #1: Accessing Homeownership is Nearly Impossible

America has long been a country where people aspire to homeownership. While the majority of Americans (66%) own a home, the median homeowner skews wealthier and older than the median American. Only 43% of people aged 25-34 own a home, while 77% of those 65 and up do. Homeownership is especially aspirational when you zoom in on cities. In urban areas, only 53% of the population owns a home, while 72% of suburban/small town residents and 80% of rural residents do:

That said, its even more unattainable in LA than other urban areas: only 49% of LA county residents and 36% of LA city residents own a home. For comparison, Fairfax County in Virginia has a 70% homeownership rate, San Diego County has a 56% rate, and even the city of San Francisco has a slightly higher 39% rate.

Why is homeownership so unattainable in LA? LA doesn’t have the highest home prices. Bay area cities like San Francisco and San Jose have higher prices. However, attainable homeownership is about more than just the sticker price; it is how that price compares to income. This is why analysts look at the “Price-to-Income” ratio, which compares prices to median incomes. Different datasets peg this ratio between 10.9 and 12.5, meaning it would take 11-12.5 years of income in LA to afford a home’s total sticker price. This explains why LA is in the top echelon of the most expensive housing markets in the US.

Notably, this is almost twice as high as other affluent, expensive, and growing cities like Seattle (7.3), DC (6.0), and Austin (6.0). And while housing in LA has never been cheap in recent history, it is far worse than it was 12 years ago. A home worth 300k in 2012 is worth 800k today, 2.67x its original price. Meanwhile, wages have only increased by 34%, which has caused the price-to-income ratio to double in the last 12 years:

This impacts people across the board, especially younger families in the middle and working class. People with stable working-class jobs will never be able to afford homes in this context, and even upper-middle-class families will often be forced to forgo buying or buying homes that are smaller than their family would otherwise comfortably live in. According to demographic research, many are simply giving up on California altogether. Between July 2010 and 2022, California saw 8.5 million residents move away to other US states, while only 6.3 million people came to California from other states - a net exodus of 2.2 million people.2

Unfortunately, as I wrote early this year, many of the policy measures that are popular and frequently proposed to close this homeownership gap do not scale up effectively.

Grants that help with down payments may help the people who receive that money, but only at the expense of others, since those grants often serve to increase the purchase price of new homes. Regulating institutional investors can bring down prices a bit, but since institutional investors are a very small portion of the market, they cannot do much, and this increases the cost of renting.

The only way to sustainably make homeownership more affordable in an economically dynamic city is to build more homes..As long as there are more people who want to buy than people who want to sell, prices will increase. Aside from a catastrophic economic crash similar to 2008, that is the only policy solution that will prove scalable and effective. The best way to do that is to build more, especially homes attractive to families hoping to become homeowners.

The traditional single-family home that has been the norm in Los Angeles is objectively the most expensive housing. They are also extremely hard to build in the city, given the relatively small amount of vacant or underutilized land. Thus, the best strategy for increasing the homeownership supply is to redevelop existing single-family homes into “missing middle” housing. Many types of missing middle housing are more affordable options, such as townhomes, cottage courtyards, and condominiums.

Middle housing was built alongside single-family homes in LA for most of its early history but has seldom been built since 1945. Multiplexes, townhomes, and small-scale apartments are de facto banned due to zoning on three-quarters of Los Angeles’ residential land. Even if they were allowed via zoning, the Terner Center recently found that for-sale condominiums are only 3% of new multi-family housing in California, while in Canada, they make up 40% of new multi-family construction.

Without reforming the liability law, which makes it too risky to build multi-family condos, the only condos that make financial sense for builders are very expensive, high-end condos. Reversing these trends should be an extremely high priority if the city wants young middle-class families to aspire to home ownership again.

Taking small steps is not impossible: consider the success of Houston in building townhomes.3 As I wrote earlier this year in our housing and climate white paper:

A powerful example comes from Houston, TX, which has a history of sprawling land use much like Los Angeles. While its urban planning mistakes mirror those in cities around the country, Houston is unique in its conviction to reform the policies that created sprawl in the first place. In the late 1990s, Houston’s government shrank minimum lot sizes laws—a historic hold over of zoning that aims to exclude—throughout the city, allowing more efficient and affordable forms of housing to be built.4

Houston’s efforts have borne fruit throughout the city: it has successfully densified its urban core and inner-ring suburbs, with most new housing being built in high-resource neighborhoods. Since implementing the reform, nearly 80,000 townhomes—a more affordable and efficient form of housing that offers many of the traditional financing advantages of a single-family home—have been built in high-opportunity areas of the city that were previously exclusively single-family homes. Despite minimum lot size reform taking place city-wide, most of the new housing and density was built in high-opportunity areas that had historically opposed new housing, demonstrating how uniform upzoning will result in equitable outcomes.

Los Angeles can and should start a similar policy program today -- we simply need the political will.

Crises #2: Lack of Affordable Rental Housing

Alongside homeownership, rental housing in LA has become increasingly unaffordable. 64% of Los Angeles residents are renters, and renters tend to be younger and lower-income than the city as a whole. This makes them more vulnerable to sharp changes in prices or incomes and, thus, more vulnerable in the broader housing crunch. Why is rental housing becoming less affordable in Los Angeles? Similar to homeownership, the core problem is a lack of homes. But unlike homeownership, affordable rental housing has two distinct meanings that can lead to confusion when we discuss how many units are on the market.

The first type of affordable housing is units that are “deed-restricted,” meaning that when they are built, the rents are capped at a level determined to be affordable for a period of many decades (usually 55 years). These types of homes have a huge impact on lower-income households because they create stability and allow them to stay in place for a long time. Unfortunately, because they usually require subsidies, they are rare. From 2013-2022, the city of LA permitted a grand total of 29k of these units, only 15% of all housing units permitted in that time period.

On the other hand, LA City has more or less stumbled into an alternative way of doing things, causing an explosion in this type of housing. Since early 2023, close to 20,000 new legally restricted affordable homes have been proposed in LA, the majority of which have no public funding. These homes are being built by private developers, who found that there was a business model in combining state and city laws; building legally restricted affordable housing allowed them to build more homes at lower cost, and get expedited approvals from the city, a phenomenon I outlined here:

Unfortunately, the LA City Council has been looking for ways to make ED1 less powerful in recent months, which is the exact opposite of what they need to be doing if they actually care about vulnerable renters.

Even with the influx of ED1 units, the vast majority of affordable housing in LA is what is called “naturally occurring” affordable housing. This is not housing that is required to be affordable by law, it is on the normal housing market, but rented at a lower cost. Deed-restricted affordable housing tends to be very expensive to produce, costing between 600k and 1 million dollars per unit for new construction, and subsidies are what make the units affordable. Naturally affordable housing is the opposite: it is cheap because it is less desirable on multiple fronts. The buildings tend to be:

Small units in less desirable locations.

Old and poorly maintained

Having fewer amenities like on-site parking or air conditioning

Historically, Los Angeles has been a city filled with this kind of older, poorly maintained housing. In unincorporated East LA, the median home was built in 1948 and many are in poor condition. In the city overall, 75% of medium and large buildings (7500 square feet and up) in LA were built before 1978:

The paradox is that older housing like this is often bad for tenants,, but that keeps rents low.

Unfortunately, the failure to build new housing has had a huge impact here. People who come to LA have gradually lowered their expectations for the housing they would consider living in. Consider the family of 6 that I met at the park: living in a 2 bedroom apartment is far from ideal, but it is a place to live in the city. As more middle-class families stay in the rental market longer, the demand for rentals means that landlords raise prices on their previously naturally affordable units. Since 2020 alone, over 32,678 previously naturally affordable units are no longer affordable to lower-income households. This is happening across the region, but especially in “higher-opportunity” parts of the city, where residents are deciding that older, naturally affordable housing is a good way to retain access to other amenities in those locations:

Worse yet, there are 140k currently affordable units that will disappear in Southern California if the housing market persists in its current direction:

One can visualize how this happens: well-off residents decide that instead of moving to the Hollywood Hills, they will move to Echo Park. Middle-class residents decide to forgo Echo Park to move to Boyle Heights, and the longtime naturally affordable housing in Boyle Heights doubles in rent. Policies designed to protect tenants, and efforts like community land trusts that focus on acquiring and preserving these units off-market can and do slow the process down.

The problem is that as long as there is a scarcity of new homes, LA’s naturally affordable housing stock will likely gradually disappear. The only way to reverse this is to build more rental stock at all income levels. New housing cannot directly replace naturally affordable housing without subsidies: because it is built to modern codes with modern amenities, it will be more expensive to build. But new market-rate housing is still vital can redirect pressure away from naturally affordable housing, especially if it is built at scale in high-opportunity areas of the city.

Again, LA should see the success of ED1, and the city should continue to make it easier for builders to construct rental housing throughout the city. They can do this by following those three simple principles: allow more homes on a single plot of land, require less costly amenities, and give short and predictable time frames for approval. ED1 would be stronger if this streamlining was broadened to include market-rate and mixed-income housing, which, even though not itself affordable, will help by housing the middle-class families that are now moving into naturally affordable units.

Crises #3: Flow of People into Homelessness

Lastly, LA has a long-standing crisis of homelessness. According to the 2023 Point in Time (PIT) count, LA County had the 2nd largest homeless population of any jurisdiction in America, with more than 75,000 people in our county currently living without a home. This also means that LA County alone accounts for roughly one in every nine homeless people in the whole US. If one just looks at unsheltered homelessness, LA County alone accounted for roughly one in five (20%) of all unsheltered homeless people in the whole US.

Yet, we have reason to think that the official numbers understate the scale of the problem by failing to account for the spectrum of situations included in homelessness. Most people’s mental image of homelessness is that of “chronic” homelessness, i.e., people who have lived on the street for over a year and have some sort of disability (which includes both addiction and mental illness). These people tend to be the most visible on the street and have the most profound needs, but they are also only a tiny fraction of the broader homeless population.

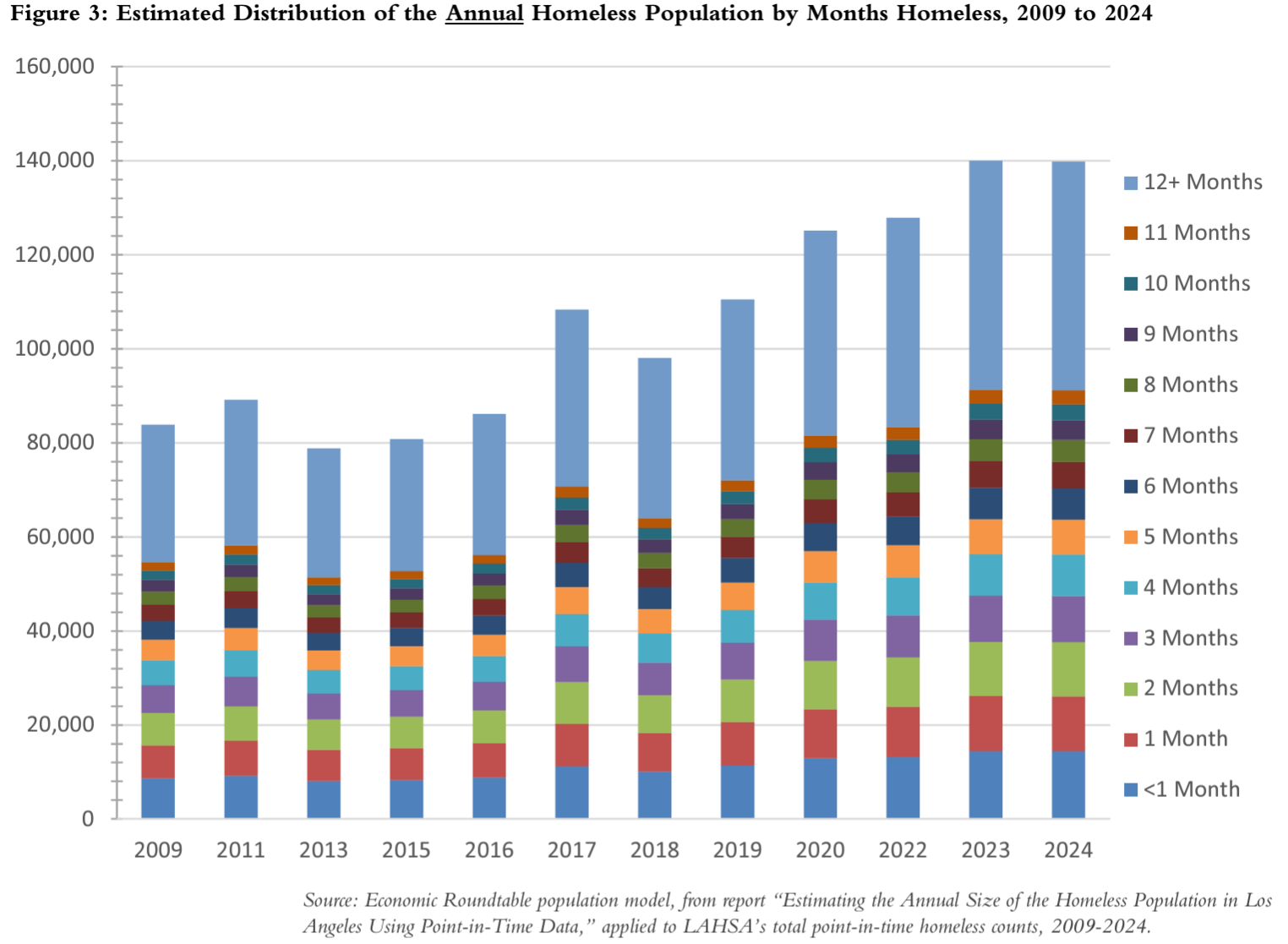

Most people who become homeless in a given year will only be on the street for a short period. Even in LA, where it is very hard to find cheap housing, a recent report from the Economic Roundtable found that in 2023 and 2024, there will be 140,000 people who experienced homelessness at some point during the year, and about two-thirds of them will be homeless for less than a year, with about 40% being homeless for less than four months (short-term):

We also know that LA has many individuals who could be called “couch homeless,” which includes people who have lost housing or cannot pay rent on their own but have a temporary place to stay or room to share. A report by the Economic Roundtable in LA found that at any given time, roughly 127,000 people are “couch homeless,” which means they are at risk of ending up in a shelter, or unsheltered on the street when their temporary housing situation fails. While there is likely to be a fair amount of overlap between these 127,000 people who are couch surfing and the 140,000 people who will be homeless at some point in 2024, attempts to blend these numbers estimate that this implies over 200,000 people don’t have stable housing of their own in LA county in 2024.

Additionally, this report points to the enormous number of rent-burdened Angelinos who are on the verge of losing their housing: “nearly 53% of renters who are in poverty spend 90 percent or more of their income for rent.” This implies that 7.4% of all city residents (~300,000) and 5.7% of county residents (~570,000) are in severe danger of becoming homeless in the near future.

Thus the following is an illustration of the range of situations that define homelessness, from the chronically homeless to those who are at severe risk of homelessness:

The water line in the above graphic illustrates the point where homelessness becomes visible as cases become more severe, and that is only a fraction of the broader problem.

What does this imply for housing? Homelessness is a complex phenomenon with both individual and policy causes. The most commonly cited causes are mental illness and substance abuse, but other factors like job loss, very low incomes, and family breakdowns all play a role. But when one steps back and looks into why certain US cities (like LA) have a hugely disproportionate number of people who are homeless, the big story is that cities with high housing costs almost universally have high rates of homelessness.

Now I want to try to make a key distinction here: there is an ongoing and pretty heated debate in the homeless policy world about a concept called “housing first.” Housing first argues that the best way to help people who have already been on the street for a long time is to prioritize housing them, not getting them into treatment – whereas other advocates will point to the need for treatment and sobriety housing. Likewise, there is an ongoing debate about priorities: some advocate for prioritizing people with the deepest issues first, while others advocate for prioritizing more stable people who will not tie up the system’s resources for a long period of time.

Whatever you think about these debates - I want to argue that all efforts to work on homelessness become harder when the broader housing market has so few low-cost options. We see this in two ways:

First, getting people off the street has become extremely difficult because of the lack of housing options. The sheer number of housing-insecure people alongside chronic homelessness makes it extremely difficult for the social workers who manage the system to sort out who simply needs housing and who needs deeper help with deeper issues. Unfortunately, many of the issues that drive a person into homelessness (family breakdown, low income, addiction, etc.) tend to become worse the longer that person stays on the street. For example, people suffering from moderate substance abuse problems are likely to spiral out of control the longer they are on the street.

Second, housing pressures are becoming more severe, making intervening harder. An emerging body of research suggests that small cash payments can effectively keep many households from falling into homelessness. But as more people become housing insecure, it is harder to target the money to those in the most need. Instead, the region has been spending billions of dollars to try to get people off the street and finding only moderate success.5

Thus, it is not surprising that recent research from all sectors and across the political spectrum have found that the biggest single predictor of the number of homeless in a city was the relative expense of housing:

Academic Gregg Coburn’s book Homelessness is a Housing Problem found that median rents explained 55% of the variation in point-in-time counts across US cities.

The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) built a research model to predict city-level homelessness, finding that housing market factors predicted between 68% and 82% of the variation in homelessness.

The American Enterprise Institute found that housing market pressures explained 78% of the variation in homeless counts and 89% in US counties with over 1 million people.

This research should not be seen as arguing that housing is the only cause or solution to homelessness. It instead argues that any strategy that tries to address homelessness in LA without building more housing at all income levels is doomed to fail.

I want to highlight AEI’s research specifically because their findings were the most counterintuitive. The variable they found was most predictive of homelessness was not evictions or even rents but the home price-to-income ratios, as I explained earlier in exploring the homeownership crisis in LA.

Here are the largest counties in the US; graphed by their price-to-income ratios on the X-axis, and their Homeless rate per capita on the Y-axis (with LA highlighted):

What is notable about this particular measure of correlation is that the median home price in a city would not seem to be inherently linked to homelessness: - after all, most people pushed into homelessness in a city like Los Angeles are vulnerable renters, not people on the verge of homeownership. The housing types most needed by people who are on the verge of homelessness are very low cost options, like low-end ADUs and single-room occupancy co-living homes, which have largely been banned in LA for most of the last half-century.

But we also should recognize that this data is telling us there is an inherent link between the plights of different classes of people with different housing crises. When middle-class families cannot buy homes, they put pressure on the rental market. This means stable working families will end up stuck in naturally occurring affordable housing, taking these less desirable units off the market. This, in turn means that renters who have vulnerabilities like very low incomes, addictions, or family breakdowns have nowhere to go when they lose their housing.

I think this dynamic is best illustrated by this video produced by the Sightline Institute in the Pacific Northwest, comparing the housing market to the game of musical chairs:

Framing the broad housing crisis this way demonstrates that while these population segments are different, they are best addressed as part of a package that works to broadly increase the amount of housing across the market at all income levels.

Thankfully, this also points to the solution: broadly work through the housing market at all income levels to make both homeownership and renting affordable for people at all income levels. If LA took this lesson to heart, you could solve all three of these housing crises through a suite of policies that interlock to address housing supply at all income levels.

This is where LA City’s Citywide Housing Incentive Program should come in. But sadly - it has far too little ambition. In Part 2 I will describe exactly where it falls short.

The process is called RHNA: Regional Housing Needs Assessment and it has some serious flaws, not all of which I will go into. At its core, RHNA has a laudable purpose of trying to give cities a kind of “growth budget” that forces them to plan for growth without the state overriding their ability to use discretion in how and where cities build that housing.

These numbers do not account for births or net migration into the US, which explains why California’s population has not fallen by 2.2 million overall.

Houston townhomes are a useful model, because Houston allows them to be built without a condo association, and to a height and density that makes them more profitable to build than single-family.

Lot-Size Reform Unlocks Affordable Homeownership in Houston. (September 2023). Pew Charitable Trusts. (Link).

LA voters passed measure HHH in 2016, a 1.2 billion dollar bond to build homeless housing, only to see the cost of new units exceed $600,000 per capita, and project completion timelines take 3-4 years. The City controller laid out the many problems in a report here https://controller.lacity.gov/audits/problems-and-progress-of-prop-hhh