My Case Against Prop 33

Everything you wanted to know about the most important ballot measure in CA

As I prepared for the election this year, I debated the merits of posting my ballot publicly. I ultimately decided not to, but I did want to highlight one particular proposition: Proposition 33. I think it is the most impactful proposition on California’s ballot this year, and some polling shows it could be a close vote. So, I wanted to take some time to explain how I will vote and why.

Prop 33 is not about rent control—to be precise, it is a measure that would roll back a state law (Costa Hawkins) that limits cities' ability to implement whatever form of rent control they desire. If this sounds familiar to Californians, this will be the third time since 2018 that Californians will vote on rent control on their state ballot. Michael Weinstein of the AIDS Healthcare Foundation funded all three. Weinstein is a mercurial mainstay in Los Angeles and California politics (more on him later).

Significantly, though, the landscape for renters has just worsened year after year since that original measure hit the ballot in 2018. As I covered extensively in a recent post, the cost of housing has continued to escalate since 2018:

I suspect that some will approach Prop 33 with more openness than the previous versions of rent control simply because the housing situation in the state has deteriorated. Unfortunately, voting “yes” would be a big mistake. I am worried about the impact Prop 33 will have on the California housing market. I am not alone in this: some of the most widely read housing commentators I know here in LA, including Joe Cohen and Shane Phillips, have written about their opposition to Prop 33. Housing advocacy organizations, including CA Yimby, Abundant Housing, and YIMBY Action, have endorsed No on Prop 33.1

I am going to explain three arguments against Prop 33 - all of which are, in and of themselves, good reasons to vote no, but together they present the most robust version of the case:

Rent control is not a path to sustainable affordability

Prop 33 allows the worst kind of rent control

Prop 33 enables bad actors

Rent control is not a path to sustainable affordability

The most straightforward reason to vote against Prop 33 is that rent control has proven to be a poorly suited policy to achieve broad affordability in housing markets. To briefly summarize, areas with affordable housing markets have three characteristics, listed in order of importance:

First and most importantly, they have flexible regulations allowing housing to come online quickly and cheaply in all city areas.

Second, they use their resources (or resources from a higher level of government) to fund subsidies to ensure that low-income families do not pay most of their income on housing.

Third, they ensure that renters have targeted protections that help them achieve stability.

Now, rent control advocates are right to point out that a rent control policy can play a part in achieving goals 2 and 3 for specific segments of people. Research has shown this: for instance, Manny Pastor, a social scientist at USC, found that in LA, rent control was central to many working families' ability to afford to live in LA as their neighborhood’s rents rose. Quite literally, his study finds that rent control keeps rents lower in units where the policy applies, which is worth remembering in the debate. This can be especially important for low-income seniors, who tend to be less inclined to move and are on fixed incomes. Economist Rebecca Diamond found that rent control in San Francisco was beneficial to older long-term residents precisely for these reasons. In a city like LA, it's hard to imagine a senior citizen who retired on wages earned in the 80s and 90s being able to afford rents at levels that have been fixed since the market of the 1980s and 90s. It is much harder for them to find affordable rent in the 2020s. If they were to lose their rent control, it would likely involve many being pushed out of the city or, worse, pushed onto the street.

I would reframe this: rent control’s main benefit is to create stability and predictability in the lives of renters. Shane Phillips describes the benefits of rent control this way:

Renters in America live incredibly precarious lives, with most being subject to unrestricted rent hikes — 10%, 20%, 50% in a single year — and to eviction at any time, and with little notice. Neither rent control nor rent stabilization solve this problem entirely, but they dramatically improve tenure security compared to the status quo. Cost savings aside, there’s immense psychological value in knowing that you can stay in your home if you choose to and having some certainty about how much your rent payments will grow year-to-year.

I have seen the impact of huge swings in the rental market on working families. It is important not to dismiss these benefits. Stability allows families to form and sustain community ties, something that economic analysis may not detect. It is also worth noting that other policy programs provide stability for homeowners. For instance, the 30-year fixed mortgage is very popular because families can lock in their mortgage payments for 30 years. Most people in the US don’t realize that this option is relatively unique to the US, and it requires extensive subsidy and regulation to make it work. Similarly, California has Prop 13, which is a kind of tax subsidy for older homeowners, who often pay a fraction of the taxes that the younger families living next door pay. This is not a fair way to approach housing, and we should reform both approaches:

I understand why a renter would ask why it is fair to have government policies that create stability for homeowners (who tend to be wealthier) but not for renters, especially since homeowners have been largely shielded from the impacts of housing scarcity in cities like LA.

But two wrongs don’t make a right, and when it comes to rent control, we have to ask whether the costs of the policy are outweighed by the benefits provided.2 And when it comes to rent control, there is one considerable cost: rent control has been shown repeatedly to decrease the amount of rental housing on the market. It does this consistently in two ways:

First, it reduces the rate of building NEW housing in a city.

Second, it contributes to the removal of existing housing from the market, either by converting it into a condo (as in San Francisco in the 1990s) or allowing it to deteriorate and become uninhabitable.

Given that building new housing is the most essential variable in a city's long-term affordability, rent control becomes a question of weighing the value of short-term stability against long-term affordability.

It's also true that the main benefit of rent control is stability for tenants, which often does not benefit the people who need it the most. I know many relatively well-off young professionals in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York who live in rent-stabilized units (as I did in LA from 2014-16). Empirical studies of rent control in St. Paul illustrate this:

I have nothing against these people and their desire for housing stability. Still, they are not the people society is trying to protect with rent control, even though there is some evidence that landlords of rent-controlled units discriminate among their tenants.

On the flip side, rent control also has little benefit to vulnerable people who, due to life circumstances, are unlikely to be able to possess a housing unit for an extended period. In Los Angeles, some of the groups most prone to homelessness are veterans, people coming out of prison, and foster youth aging out of the system. What unites people in these disparate circumstances is this: they are confronted with the challenge of finding new, affordable housing after not living in a housing unit for a long time. Foster youth suddenly need to live independently when they turn 18, veterans need housing when they return from deployment, and those returning from prison after release. They are almost certainly hurt by rent control because the scarce number of rent-controlled units they need are occupied by more affluent folks in their city.3

Economists overwhelmingly oppose rent control when the costs and benefits are weighed against each other, as economist Jay Parsons describes. A 2012 IGN survey found that 95% of economists said rent control harms housing affordability in the long run:

This is not a partisan divide - the survey included many left-of-center folks like Emmanuel Saez, Daron Acemoglu, and Raj Chetty. A 2024 survey on Joe Biden’s national rent cap proposal found similar levels of opposition.

This is not surprising. One of the fundamental tenets of the discipline of economics is that the government is not very good at setting prices - which is the goal of rent control. Most of you reading this don’t care about the theoretical assumptions of pointy-headed economists. However,t a fundamental insight is embedded within this principle: prices in a market are based on incredible amounts of information and negotiations between different economic actors. In the real world, this usually plays out as economics would predict. Consider a host of real-world examples from around the globe:

Mumbai, India, has a strong rent control policy that can even set building rents below $10/day. This policy has contributed to the frequency with which buildings collapse due to deferred maintenance.

St. Paul saw housing construction drop precipitously after passing rent control in 2021, even as its twin city, Minneapolis, kept building.

The wait time for a rent-controlled unit in Stockholm, Sweden, is 9.2 years on average and as long as 20 years in some cases.

Argentina had very strict rent control in Buenos Aires, and when it was recently scrapped, the housing supply increased by 170%, and rents dropped by 40% after adjusting for inflation.

To put the question another way, is it better to be a low-income person looking for housing in Houston (no rent control):

Or LA (with rent control)?

I would guess most would choose Houston. Houston makes it very easy to build new housing, including rental housing that can help folks coming off the street out of homelessness:

Houston also makes it easier to build starter homes that can help middle-class families buy a home, thus freeing up rental properties for families who are more in need:

Prop 33 allows the worst kind of rent control

Now, it's also true that there is some nuance: after all, not all rent control is created equal. Tokyo is the biggest success story in keeping an economically prosperous city affordable, and it has a form of rent control. Conversely, Southern California suburbs like Glendale and Irvine are just as unaffordable as LA, yet they do not have rent control.

The reality is that a host of policies impact housing production far more than rent control. Forms of land use regulations that directly impede housing construction are far more important in most cities. Most of Orange County, California, is hostile to rent control but still has stringent exclusionary zoning, making it impossible to find affordable housing there.

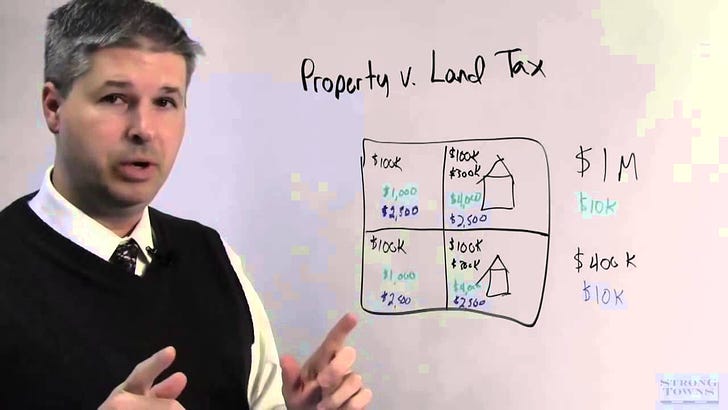

The other important nuance is that while rent control always has some adverse effects on supply, some types of rent control have much stronger effects than others. Economist Richard Arnott made a conceptual distinction by discussing “first” vs. “second” generation rent control.4 This is also sometimes discussed as the difference between rent control and rent stabilization. For the sake of simplicity, I will focus on two factors that are important to discuss in the context of comparing rent control regimes:

The first factor is whether new construction is exempt: Building new housing is risky, even in a hot market like Los Angeles. Unclear approval timelines, out-of-date zoning rules that require haggling with the planning department, and even factors like interest rates and construction costs varying year to year combine to make building very risky if you are not careful. Telling a developer your city will control the rent they can charge starting day 1 is a surefire way to make developers decide to develop housing in the city next door because it minimizes their risk. This is precisely what happened in St. Paul when they passed rent control in 2021, which did not initially exempt new construction; developers shifted to building in Minneapolis instead. This is a horrible outcome since new construction is crucial for sustainability and long-term affordability. So, most second-generation rent control regimes try to avoid this by giving developers an extended period (i.e., 15 or 30 years) for which no rent control will apply. This doesn’t reduce their risk to zero but reduces it compared to rent control on new construction.

The second factor is vacancy control. First-generation rent controls are permanent even when a tenant moves out. So if the former tenant paid $1000/month, and rents increased by only 5% a year, the next tenant would only pay $1050. Vacancy de-control means that when a tenant moves out, the rent resets to market rate, freeing up the landlord to upgrade or renovate a unit. As Joe Cohen writes, this flexibility becomes very important as an incentive for existing units to stay as rental housing (not converted into condos), to be maintained rather than deteriorating, and most importantly, for new housing to be built in the first place.

Cities like Tokyo that maintain some level of rent control and yet build enough new housing to make housing affordable all have second-generation rent control. Conversely, cities like Stockholm and St. Paul, with severe housing shortages, have forms of first-generation rent control. We must avoid first-generation rent control if we want a functioning housing market. California’s state legislature has tried to avoid first-generation rent control through a series of compromise bills, primarily through two laws:

1) Costa Hawkins, passed in 1995, would be repealed under Prop 33. Costa Hawkins broadly prohibits cities from passing rent control ordinances that are “First Generation,” i.e., ordinances that put rent control on new construction or allow vacancy control.

2) AB 1482 or State Rent Cap, passed in 2019, created a more modest form of rent control across the state, limiting rent increases in California to 10% a year OR 5% plus inflation, whichever is lower. It exempts properties built in the last 15 years, and gives renters some rights limiting the ability of landlords to evict them.

One can visualize these as a kind of ceiling and floor of rent regulation: Cities are supposed to stay between this floor and ceiling in the way they approach rent control:

Readers may wonder if these two laws went too far in one direction or another. For the sake of not getting bogged down on questions that are not on the ballot, I will say that this is not how I (or most economists) would have done it if we could create policy from scratch. But policy is never made from scratch, and it is hard to imagine current rent stabilization policies being suddenly rolled back without harm.5

While tenant rights advocates are right to point out that the current system has “loopholes” that limit the reach of rent control, it is crucial to point out that these loopholes were explicitly designed to prevent rent control.

This is precisely why Prop 33 would be a step back for housing: rather than accepting this compromise and attacking the root cause (the need to spur new construction), Prop 33 gives cities carte blanche to do whatever they want. The law explicitly prevents the state from interfering with "the right of any city, county, or city and county to maintain, enact or expand residential rent control." Prop 33 could send cities down a destructive trail of experimenting with vacancy control and regulating rent on new construction.

Prop 33 enables bad actors

For people who are not convinced by reasons 1 & 2, it's essential to be very clear about why Prop 33 is on the ballot: bad actors put it there. Michael Weinstein, who financed the measure, is the leading bad actor here. He runs the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which federal law allows to buy drugs at a considerable discount because they serve low-income patients. They are supposed to spend the difference between their revenue and their cost on providing patient services. Instead, Weinstein has spent much of the organization's 2.2 billion in annual revenue on various political campaigns. At the same time, Weinstein operates horrible substandard housing for low-income tenants with minimal oversight due to insiders like Kevin De Leon, who enjoy lavish funding from Weinstein.

What is Weinstein’s housing agenda? He is convinced that he understands housing policy in the state alone and believes that he can help low-income people in California by opposing new housing development. Thus, his decision to sue the city over various new housing developments in Hollywood, his decision in 2017 to propose Measure S, which would have put a moratorium on all new development, and his active campaigning against statewide housing bills, using less than honest tactics. Weinstein is such a notorious figure that Proposition 34 was written to get him out of politics and back to actually doing healthcare for vulnerable people.

So it's not a surprise that Weinstein does not care about the impact of this proposition on the state’s housing supply -- Weinstein doesn’t want new housing to be built. What is more interesting is how other cities have come alongside him to support this while saying the secret part out loud: they believe this will kill housing production. Consider Tony Strickland, a Huntington Beach Councilmember and a Republican who generally opposes rent control. Strickland raised eyebrows earlier this year when he supported Prop 33, saying that he believes it will make it easier for the city to avoid state requirements to build housing, as the city has been trying to avoid for years.

Other wealthy cities are almost certainly taking note (though they are shrewder about not publicly signaling their motivations). Some will devise creative ways to make being a landlord so annoying that all rental units are turned into condos, leaving renters with nowhere to go. Left-wing cities like Pasadena and Santa Monica will probably dress this up in social justice language, and right-wing places like Huntington Beach will claim they are defending homeowners’ rights (and both should be ashamed). Before you dismiss this as farfetched, consider that Woodside, a wealthy Bay Area suburb that hosted a recent Joe Biden/Xi Xingping summit, tried to get the whole city classified as a mountain lion refuge to avoid state housing law. Consider how historic preservation overlays spread across wealthy cities to avoid state law.

How would this play out? Well, consider how California has overridden city rules to make it easy for homeowners to build AccessoryDwelling Units (ADUs) in their backyards. This has been a popular policy that has spurred lots of new housing across the state. From what I can tell, the only people who do not like state ADU reform are the local bureaucrats because it was an incursion on their turf. This was especially true in wealthy cities like Pasadena, where ADUs were resisted for a long time. If Prop 33 passes, affluent cities like Pasadena may comply on paper with state law by allowing for ADUs to be built but kill the financial incentives by layering them with so many rent regulations that no homeowner would consider creating them. The state could do nothing to crack down on this behavior due to the language in Prop 33, which explicitly hamstrings the state legislature from reversing the measure.

This is a shame because while the state legislature in California is not perfect, they have been working very hard at making housing more affordable in recent years. They have been passing laws and consistently revisiting laws to tweak them when they do not work as intended. This is something voters seldom can do to ballot measures, given how hard it is to raise the money necessary for a ballot measure. Regardless of your position on rent control, there is nothing stopping reformers from working with state lawmakers to encourage further reform. If you want a stricter version of rent control, you could have the state work on that. While I don’t support more stringent rent controls, there are compromise proposals that I could be open to if paired with a policy that spurs production.6 The state legislative process will allow for a controversial issue like rent control to be crafted through compromise and dialog rather than a radical change that opens the door to bad actors.

I have relied on their work to put this together, so kudos to them!

Consider how, if we wanted to control crime, local governments could make a ton of progress imprisoning every male between the ages of 15 and 30 who has ever broken the law. After all, men in this age range commit most crimes! But even the most tough-on-crime conservative would hopefully see that this would be utter madness due to the violation of rights and cost to society.

This is why actual subsidies that follow individuals are a much better tool for affordability than rent control, which follows units.

Advocates sometimes cite Arnott as supporting 2nd generation rent control - though this is not true. He later would make clear that he did not support rent stabilization; he believed it was qualitatively less harmful: https://cityobservatory.org/what-we-know-about-rent-control/

In 2020, I compared rent control is similar to employer-based health insurance for its inefficiency in policy design. Getting healthcare from your employer forces you to stay in jobs you don’t want and discourages entrepreneurship. Having rent control follow units discourages tenants from moving. Ironically, both programs were installed as temporary measures during World War II but were accidentally permanent. It's also a reality that as both have become permanent fixtures in the policy world, people build their lives around them, making it very hard to reform without hurting vulnerable people. One could make a "small-c conservative" case that if we do reform these policies, we should do so incrementally to avoid harms inevitably done unintentionally.

One idea I support in theory is a compromise where Costa Hawkins becomes rolling, i.e., buildings can have rent control for 30 years after being built instead of having a hard cutoff at specific years in current law. To make this net pro-development, you would also want to see measures that would make it easier to replace older rent-stabilized buildings. This would be difficult, as existing tenants would need some protections to ensure they don't lose access to affordable housing, but I think it could be done.